|

|

Materialist Apologetics

by Francois Tremblay

I. The General Argument

II. The ‘Inherent-Property’ Objection

III. Comparative Analysis

IV. Illuminating a Presuppositionalist Example

I. The General Argument

In my “Handbook of Atheistic Apologetics”, I propose a division of atheistic arguments in five categories: semantic apologetics, incoherency apologetics, materialist apologetics, memetic apologetics and evidential apologetics. I think this is a useful classification, and echoes the Christian classification of theological arguments.

In that view, what I call materialist apologetics, which is in essence an extension of the TANG, is an atheistic stance on Christian presuppositional apologetics. I refute presuppositionalism in my obviously-named article ‘Why Presuppositionalism is Wrong’. Basically, presuppositionalism states that atheists are fundamentally unable to explain various features of human understanding – logic, consciousness, induction, scientific laws, morality, meaning, and so on – and that only theism can provide an explanation for them.

In the article, I prove that the premises of this “fundamental inability” are logically faulty, and that the conclusion of presuppositionalism is also flawed in many different ways. This article is not, however, about disproving presuppositionalism, but rather about proving the atheistic position that I call materialist apologetics. Materialist apologetics is based on the contradiction between the necessity of various features of human understanding, with the contingency that arises from divine causation, making atheism the sole reasonable alternative.

I do briefly discuss this line of argumentation in point 1 of “Why Presuppositionalism is Wrong”, giving the TANG. I will do so here also.

We can express the general materialist strategy as such:

Posit X is a feature of human understanding.

- X is necessary or has a necessary part.

- If theism is true, then divine creation obtains.

- If divine creation is true, then all in the universe is contingent to God’s act of creation, and nothing in the universe is necessary.

- If theism is true, then no X can be necessary or have a necessary part. (from 2 and 3)

- Theism is false. (from 1 and 4)

The beauty of this argument is that presuppositional arguments are already based on (1) and (2). Theologians already claim that divine causation is the only means we have to explain the necessity of some or all X. Therefore, all the atheist has to do to prove materialist argument is to repeat the facts of the matter as the theologian himself accepts them, but with the addition of (3).

A logical corollary of this argument is that principles and absolutes cannot exist in the theological worldview, given that they are both based on the uniformity of nature as necessary. The principles of logic, science, morality, etc. and logic as absolute, become impossible. So as a shorthand one can say that “contingency implies the impossibility of principles and absolutes”.

II. The “Inherent-Property” Objection

However logical (3) is as a deduction, an objection has been raised against it. In fact, I hear it quite commonly as an answer to materialist apologetics. Theologian John Frame, in answer to Michael Martin’s TANG, claims that:

Logic is neither above God nor arbitrarily decreed by God. Its ultimate basis is in God’s eternal nature. God is a rational God and necessarily so. Therefore logic is necessary. (http://www.reformed.org/apologetics/martin/frame_contra_martin.html)

If X is part of God’s nature, then it is a necessary consequence of divine causation. This argument seems an easy escape from the problem, since God is a necessary entity from the theological standpoint, but it suffers from a number of critical flaws.

- A critical problem is that it is absolutely irrelevant to the materialist argument. The Christian is not addressing the fact that logic becomes subjective if God creates it, he is only specifying the nature of that subjectivity. So instead of presenting a rebuttal, he is in fact supporting it ! Whether logic is part of God’s nature or not does not change the fact that it originates from a will, not from exterior reality – which is the very definition of subjective.

- Another critical problem is that the Christian has absolutely no grounds to discuss the specifics of God’s nature. Once we accept the possibility of a Sovereign, Creator being, we cannot assume anything about its properties (any more than we can posit “anarchy” and then try to define further political properties). Not only that, but the Christian cannot refute the possibility that this infinite god is deluding him into believing the statement “God’s nature is logical”. Once the Christian accepts the possibility of a Sovereign god, he can no longer refute arguments based on extreme skepticism. We can only refute the idea of a Sovereign being manipulating our minds if our worldview includes a self-contained universe.

- It is also a complete ad hoc rationalization: nothing about the idea of a god indicates that it must be necessarily logical or rational. Indeed, since humans are capable of being both logical and illogical, it seems impossible for a more powerful being to not being able to do such a simple thing as making an illogical proposition.

- Furthermore, even if that was the case, there would be no necessary relation between God’s inherent properties and its creation, and the theologian would need to prove this relation before his objection can have any weight. More specifically, one would need to prove that powerful beings are restricted in their creations. There is no obvious correlation, it is inductively unsound, and I have never seen any such attempt.

- It is impossible to make sense of the proposition that “logic is part of God’s nature”, insofar as TAG itself proposes that logic was in fact a creation of God. Logic cannot both be an intrinsic part of God’s actions and created by God.

- Frame’s objection is self-defeating. If logic existed first as a property of God, then it is a non-material principle, and divine causation is not necessary at all. All it would prove, at best, is that a non-material principle is involved, but there is a definite lack of specificity in his objection.

- The objection presumes that it makes sense to speak of logic as a non-material entity, which seems to indicate a commitment to idealism. From our perspective, logic is an axiomatic fact of reality, and arises because of the fundamental nature of the material world. It makes no sense to speak of logic dissociated from the material world, any more than it makes sense to speak of immaterial consciousness.

If the theologian is committed to this view of logic, then we have to corner him with noncognivitism. He is not using “logic”, in this case, as the feature of human understanding that we know as logic, the method of non-contradiction that arises from the singular nature of all existants. That logic must have been created along with the universe, and thus fall under materialist apologetics. Whatever the theologian is talking about, is not logic.

III. Comparative Analysis

What do all X arise from? The only reasonable answer is that they arise from the necessity of the material universe. No presuppositionalist argument has disproven this assertion, and from the rational worldview, we can discuss how a specific X arises deductively. In making a case for a specific X, we can examine two different aspects of the issue:

Positive case: We can justify X pragmatically and/or deductively.

Negative case: X is necessary or has a necessary part, which contradicts divine contingency.

An example of the negative case is the TANG. I said I would give it again, and here it is, with quotes from Matin:

- “Consider logic. Logic presupposes that its principles are necessarily true.”

- “However, according to the brand of Christianity assumed by TAG, God created everything, including logic; or at least everything, including logic, is dependent on God.”

- “But if something is created by or is dependent on God, it is not necessary—it is contingent on God. And if principles of logic are contingent on God, they are not logically necessary. Moreover, if principles of logic are contingent on God, God could change them… So, one must conclude that logic is not dependent on God, and, insofar as the Christian world view assumes that logic so dependent, it is false.”

- “Consider morality. The type of Christian morality assumed by TAG is some version of the Divine Command Theory, the view that moral obligation is dependent on the will of God.”

- “But such a view is incompatible with objective morality. On the one hand, on this view what is moral is a function of the arbitrary will of God; for instance, if God wills that cruelty for its own sake is good, then it is. On the other hand, determining the will of God is impossible since there are different alleged sources of this will … and different interpretations of what these sources say; moreover; there is no rational way to reconcile these differences.”

- “Thus, the existence of an objective morality presupposes the falsehood of the Christian world view assumed by TAG.”

- “Miracles by definition are violations of laws of nature that can only be explained by God?s intervention.”

- “Yet science assumes that insofar as an event has an explanation at all, it has a scientific explanation—one that does not presuppose God.”

- “Thus, doing, science assumes that the Christian world view is false.”

You may note that these three arguments can be translated as reformulations and extensions of the general strategy I gave earlier.

- Presuppositionalist theologians claim that logic is necessarily true. If divine causation is true, then logic is contingent. Therefore divine causation is invalid.

- Presuppositionalist theologians claim that the objectivity of morality and moral responsibility are necessarily true. If divine causation is true, then the objectivity of morality and moral responsibility are contingent. Therefore divine causation is invalid.

- Presuppositionalist theologians claim that science – or in this case, more accurately, the uniformity of nature – is necessarily true. If divine causation is true, then the uniformity of nature is contingent. Therefore divine causation is invalid.

Of course, the question may arise as to how exactly we can justify our position that all X are material and arise from material processes. We do not have the burden of proof to demonstrate how they do, but it can be important to show that we indeed can give such justification. I will give quick rundowns on the three areas of TANG, logic, the uniformity of nature and morality. Other areas can be justified similarly.

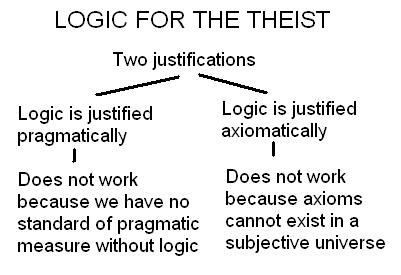

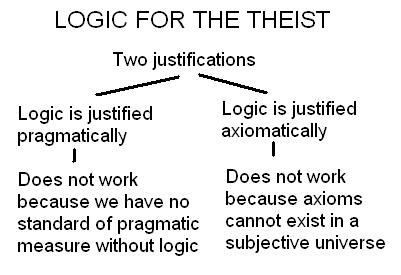

Logic: The method of excising contradictions. Without logic, we have no means to think and communicate in a non-contradictory way. Pragmatically, we can only accept logic’s validity.

Deductively, it is a consequence of the axiom of identity – that all existents have a specific set of attributes, which is called their nature. This singular nature gives rise to the principle that things are what they are, and that contradictions cannot exist, which are the basis of logic. The host of logical fallacies we know are derived from these principles also, but they reflect the multitude of situations where logic is used.

The uniformity of nature/induction/scientific laws: Pragmatically, it is advantageous for us to assume the uniformity of nature. Either nature is in fact uniform, it is partly uniform, or not at all. If nature is uniform, then assuming uniformity will always be advantageous. If nature is partly uniform, then we benefit in our assumption when it comes true, and in the cases when nature is not uniform, no method can return any benefit. If nature is not uniform at all, then no knowledge at all would be possible whatever method we use.

Deductively, we know that the uniformity of nature is a reformulation of the principle of causality: all entities effect each other according to their nature. We should not be surprised, therefore, that we can formulate scientific laws, since they are nothing more than measurements of the identity of the entities that surround us.

Objectivity of morality: We have no choice to accept at least certain objective facts of morality, if we are to remain alive at all. We all explicitly or implicitly accept that eating, sleeping, and so on, are necessary causal prerequisites for our own lives. So pragmatically, it is impossible to deny that at least certain objective moral facts exist.

Deductively, we know that morality is objective because, like any form of knowledge, it is based on the facts of reality – specifically, in this case, on the causal relationships between man and his environment, and men between themselves. We also know that, if anything exists at all, it must exist objectively.

IV. Illuminating a Presuppositionalist Example

I would like to end by looking at a more specific example, in the article ‘Rethinking Milk Buying’, by theologian Douglas Jones. In it, he describes how presuppositional principles apply to the mundane action of going to a store and buying milk.

When you first walk up to the grocery store, you assume that you and the store are two different things, not one, thus showing your rejection of most Eastern and New Age religions. When you walk down that same dairy aisle and select the same kind of milk, you assume that the world is not chaotic, but orderly, regular, and divided into set kinds of things.

When you stand in line with others, expecting others to respect your space and person, you reveal your rejection of moral relativism and your deep trust in absolute ethical norms. When you calculate your available change, compare the price of the milk, and make the exchange with the clerk at the register, you engage in a complex array of thought processes involving nonmaterial rules of reasoning, thus showing your rejection of materialism and evolution.

The first sentence is absolutely ridiculous – does Jones think that Buddhists do not go to the grocery store because they are one with it? It is hard to believe that he wrote it as anything else than a rib at Eastern religions.

The other points, however, reflect presuppositional thought on the issues of natural law, morality and thought processes. We have to return these points to Jones. Of what right does he proclaim that his worldview is compatible with these things?

From our perspective, we assume that the world is orderly, and that we can buy milk as an entity, because we know that causality is a necessary part of the universe. We expect other people to respect us because we have observed that most people have some respect for others, and we would like them to have respect because it would help support our own values. Finally, we trust our thought processes because they are based on reason, which is itself based on the necessary objectivity of reality.

How can a theologian like Jones explain his own use of these principles? If he truly believes in divine causation, which I contend no one really can, then he must hold the position that all these things are continually contingent on God’s will. It could be that the kind of milk that Jones buys changes unexpectedly, that his values become absolutely evil, and that he cannot trust his own cognition. Once the theologian implicitly denies the necessary nature of reality, he has surrendered himself to chance. We must reject this view, and the theological worldview, wholeheartedly as being the height of absurdity.

Last updated:

15/05/2005

|